What should we expect from Apple's transition to its own processors?

- 10 June, 2020 21:00

A new report claims that Apple will make a significant announcement at WWDC a couple weeks from now: a transition in Mac hardware away from Intel’s x86 processors and toward its own custom-designed ARM processors.

It is a move that makes a lot of sense, and one that has been rumored for some time. We’ve written about it several times here on Macworld.

If we assume that it is really happening this time, what would it mean? It what ways would it change the Mac, and when?

A possible timeline for ARM Macs

Just because Apple is apparently going to announce the transition to its own Mac processors at WWDC on June 22, that doesn’t mean you’ll be able to run out and buy such a Mac right then. Actual hardware isn’t expected to ship to consumers until 2021.

Apple changed entire processor architectures in the Mac twice before: From the 68000 architecture to PowerPC, and then from PowerPC to Intel.

That last transition may provide some hints into how Apple will handle this one.

Apple

Apple

Apple’s first Mac processors will likely be based on the A14 chip that will debut in the iPhone 12.

Apple announced the transition at WWDC in the summer of 2005. It didn’t announce any new Macs, however. Instead, it started selling a modified Power Mac G5 with an Intel processor exclusively to registered developers, so they could start getting their Mac apps ported over.

Then, early in 2006, Apple announced new Intel-based Macs: a 15-inch MacBook and an iMac.

It seems likely that Apple will handle this transition in a similar fashion. Developers may get some sort of modified existing Mac ahead of official new products. Maybe that will be an iMac in the rumored new design. Maybe a MacBook of some sort. But it’s not likely to be significantly different from what is offered to regular consumers with Intel processors. The whole point would be for developers to translate, optimize, and update their code so they’re ready when the new products go on sale.

What the transition means for macOS and apps

When Apple transitioned from the 68000 architecture to PowerPC, it didn’t drastically change the operating system. PowerPC support came in System 7.1, and support for the 68000 series of Macs ended with System 8.5. By the time Apple transitioned to Mac OS X in 2012, the company hadn’t sold 68000-based Macs for years.

The same thing happened with the transition from PowerPC to Intel processors. The first products shipped in 2006, running the same Mac OS X version 10.4 (Tiger), and Apple sold both PowerPC and Intel-based Macs as it made the transition. Support for PowerPC was dropped in Mac OS X 10.6 (Snow Leopard) a few years later.

During the announcement of the switch to Intel Macs, Steve Jobs said that OS X had been living a “secret double life” inside Apple. The last several versions, and all of Apple’s applications, had been made for Intel in addition to the PowerPC version. It wouldn’t be a surprise to hear Tim Cook announce the same thing, maybe even in the same way.

Apple

Apple

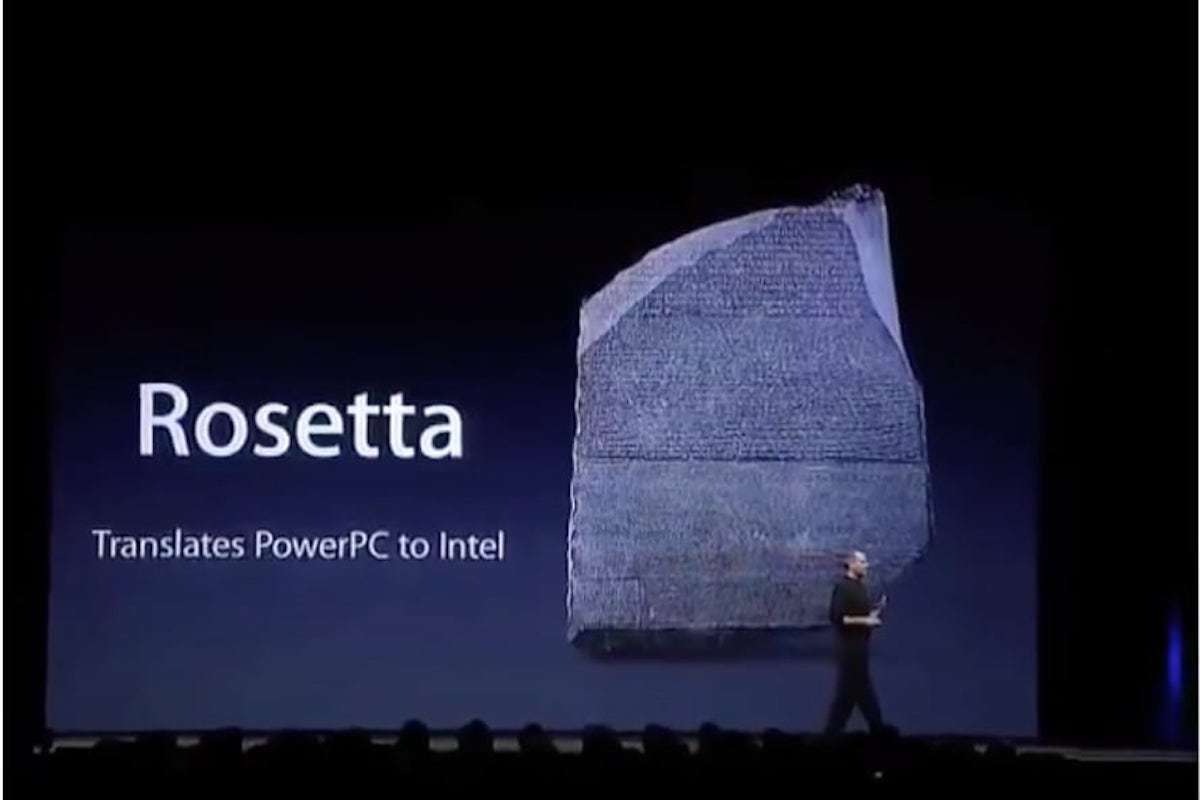

For the PowerPC to Intel transition, Apple introduced Rosetta, software that let Intel Macs run many apps written for PowerPC.

To hep ease the transition, Apple used software emulation for applications that were not re-written to support the new architecture. Rosetta was software that let Intel-based Mac owners run many apps written for PowerPC Macs. A Mac 68k emulator allowed PowerPC Macs to run software for 68000-based Macs.

In both cases, software emulation was backward-looking only. Those who bought new Macs with the new processor could run many of the applications made for the old processor, but not the other way around.

The transition to Apple’s own Mac processors should be similar. We probably can’t expect a whole new Mac operating system for a few years—not until the hardware transition is complete. In the meantime, the forthcoming macOS 10.16 will likely ship on Macs with both Intel and Apple processors, and Apple will provide some sort of software translation capability to enable some software for the x86 processors to run on the ARM processors.

Perhaps macOS 10.17 or 10.18 will only support Macs with Apple processors, and eventually, Apple will drop all support for older Macs, including whatever software emulator or translator it provides. All told, the transition will likely be complete by 2023 or 2024.

What the transition means for Mac hardware

Of course, the entire point of changing from Intel’s x86 processors to Apple-designed ARM processors is to do totally new stuff with Mac hardware and software. Not to just make faster laptops, but to change the game entirely. Perhaps Steve Jobs said it best when announcing the switch from PowerPC to Intel:

The most important reasons are that, as we look ahead...we can envision some amazing products that we want to build for you. And we don’t know how to build them with the future PowerPC roadmap.

As was the case then, the performance per watt of PowerPC’s future products was drastically worse than that of Intel’s. Apple’s own processors are similarly poised to deliver dramatically better performance per watt than Intel’s. That will enable all new form factors that Apple just can’t achieve today, and accelerate improvements in battery life for Mac laptops.

But it’s more than that. Today, iPhones and iPads enjoy features that the Mac doesn’t, and it’s in part because of the capabilities of Apple’s A-series processors. Apple invests heavily in hardware to accelerate machine learning code, and in making the CPU, GPU, and other pieces of hardware (like audio and video video encoders and decoders) worth together seamlessly. It invests heavily in hardware-based encryption and security.

Some of these things currently come to the Mac in the form of a separate T2 processor. But to really do exciting new stuff with the Mac, Apple has to take control of the whole stack. To synergistically design its silicon, its hardware, and its software.

Roman Loyola/IDG

Roman Loyola/IDG

The Mac Pro, with all its ports and expansion slots, seems destined to be the last Mac to transition to Apple’s own processors.

Apple will probably start the Mac transition with laptops. Given that the heritage of the Apple processors is the A-series found in iPhones and iPads, it just makes the most sense. Mac laptops don’t need extreme performance, don’t need expansion cards, and are less likely to be sold to people who need to use lots of external peripherals or old infrequently-updated software. And the laptop would benefit most from the lower power consumption, leading to better battery life.

From there, Apple may move “up the stack” to replace more powerful computers, eventually even the Mac Pro. That product, besides being brand new, is sold to customers that need to use niche peripherals like audio and video interfaces, who want support for internal expansion cards, and use software that may not be rapidly updated to a new architecture. Going last gives Apple, software developers, and customers time to adjust.

I would be disappointed if the first Macs sold to consumers with Apple processors in them didn’t deliver dramatically better features in some ways. I would expect a huge improvement in battery life, especially when the laptop is asleep with the lid closed. Apple has dropped the ball on its built-in webcams for years now; not to replace it with the iPhone’s TrueDepth module and provide Face ID (along with dramatically better photo and video quality) would be an incredible fumble. Other improvements, like support for Apple Pencil, could be on the table as well.

This transition isn’t like the last two

It can be instructive to look at the last two times Apple changed the Mac processor architecture in order to better understand the coming shift. We can’t make all the same assumptions today as we did then, though.

For starters, the Mac has gone from Apple’s primary product to a much smaller, almost niche part of its portfolio. Apple sells many times more iPhones, iPads, and Apple Watches than it does Macs. Those products didn’t even exist yet during the PowerPC to Intel transition.

Apple’s most popular products (by a mile) already use its own processors. The Catalyst program is already under way, bringing its most popular software development environment (iOS) to Macs.

It wouldn’t be crazy for Apple to say that Macs using its own processors will only run Catalyst apps, especially if you consider that Catalyst is likely to see some really big improvements over the next two years.

Would that leave a lot of developers behind? Would it seriously hamper the ability of new ARM-based Macs to run legacy software, annoying Apple’s longtime diehard fans?

Yes, and yes. It would be the most disruptive of all scenarios, but it would also make the transition more rapid. And despite the inevitable grousing by Apple diehards, I don’t think Apple would lose many of those customers. Many of those Apple fanatics are already earnestly defending the “iPad can be your whole computer” position, and this meets them more than halfway.

Besides, what are those Apple fans going to do, buy a Windows laptop?

More so than ever before, Apple can afford a disruptive Mac transition. It can afford, at least economically, to rapidly abandon the current Mac ecosystem in order to forge something that brings in new customers, as long as it doesn’t wait too long to give old customers what they need. It might mean depressed Mac sales for a year or two while the software catches up and the legacy enthusiasts hold on to their aging Mac hardware, but the strength of Apple’s other products makes it easy to whether that storm.